Canadian Railway Troops

Beginnings

Prior to 1914, more new railways had been built in Canada than anywhere else in the British Empire.

The C.R.T. battalions were not part of the Canadian Corps but came under the command of Brigadier (later Major General) John William Stewart, a Scots-born Canadian from Vancouver [and survivor of the 1886 fire] who became Deputy Director General Transportation (Construction) at British GHQ in January 1917.

In October 1914, Canadians had proposed sending railway units to Europe but were turned down.

The British War office requested “a corps” in February 1915.

The Canadian Pacific Railway was asked to provide their expertise, and management picked 500 experienced CPR men who had passed technical tests.

The men assembled in Saint John, N.B.

Crews consisted of: locomotive crane, blacksmith, telegraph, timber trestle, bridge derrick car, track pile driver, portable pile driver, track laying machine, concrete mixing, steam shovel, work train, dining car, and labour.

280 mules, ten lorries, and eight boxcars.

The Canadian Overseas Railway Construction Corps landed in France in August 1915, and began working in Belgium.

May 1916 saw another request by the British for 1,000 men.

Existing railheads were a dozen miles or more behind the front lines.

After the Somme, it was clearly proven that road and animal transport could not alone bring forward the weight of war material required.

Units

1st Construction Battalion to France October 1916; became the 1st CRT.

127th York Rangers to France January 1917; became the 2nd CRT.

The CRT Depot was established at Purfleet.

4th and 5th CRT were assembled from the Depot; to France February 1917.

239th Battalion to France March 1917 as the 3rd Battalion CRT.

By April 1917, 6 battalions were equipped and serving in the field; another 4 by June ’17.

By the Armistice the CRT were 16,000 strong, in 13 battalions and 4 specialist companies.

Another 3,000 men were in England.

The 228th became the 6th CRT.

The 257th became the 7th.

The 218th and 211th became the 8th.

The 1st Pioneer became the 9th.

The 256th became the 10th.

The 3rd Labour became the 11th.

The 2nd Labour became the 12th.

The 13th CRT was assembled from the Depot.

Some Techniques

At Vimy Ridge, the lines were laid on the heels on the advance. Shells and small arms ammunition came up, and casualties were evacuated.

60 miles of narrow gauge were laid. In five hours a spur line was constructed and a British battery supplied with shells the morning of April 9th.

Messines: the supply of artillery ammunition supply was so effective that the number of daily trains was reduced.

Passchendaele: over 100 light railway breaks every day, from enemy shellfire.

Cambrai: tanks were brought forward via rail and then used the railbed to advance.

Canal du Nord: 2,000 tons of rations a day were brought forward via light rail.

Steel box cars in sections were shipped over and reassembled.

Grand Trunk Pacific and Canadian Northern amalgamation saw excess rails and track supplies shipped to France.

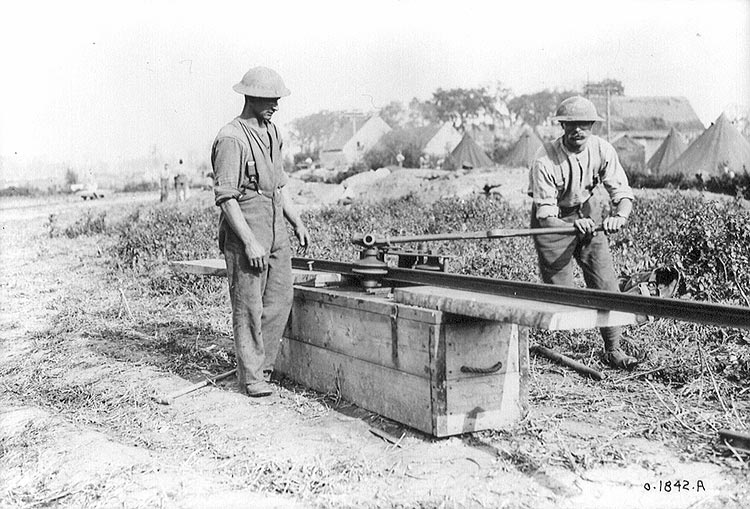

Light rail was 24” inch gauge, in pre-fabricated 11 foot long sections that two men could handle.

10 or 20 horse gas engines were used at the front.

At the rear, 16 ton steam locomotives pulled the wagons.

CRT personnel did not receive military training other than basic drill, courtesies, and protocols. Being specialists and considered non-combatants they went immediately to their work. It was assumed they knew their trades.

Action

In March 1918 during “Michael,” seven battalions were withdrawn and constructed a rear defence trench system over 30 miles frontage, with 120 miles in total trenches.

In the last days of March, 2nd CRT were called to help defend Amiens. They commandered and deployed 16 Lewis Gun teams.

The 2nd also assembled rafts of lumber and ties and floated supplies like steel rails, telephone poles, and more ties back down the canals.

Six officers and 250 other ranks volunteered for service in Palestine in September 1918, and returned to England in March 1919.

Casualties

Men were killed due to accidents, enemy shelling, and aerial bombing as well as machine guns and rifle fire. The number injured from these incidents was even greater. While the troops in the front lines had the protection of their trenches during artillery shelling, the railway troops were often out in the open. They worked above those trenches either moving supplies forward or repairing lines that had been damaged from shelling, while the troops below went about their business. The repairing of lines was a constant activity and the threat from shelling, either observed or random, was a daily occurrence.

Deaths until the Armistice – 483 in France, Britain, and Canada

Non fatal “battle” casualties – 48 Officers, 1,334 Other Ranks

Non fatal “ordinary” casualties – 23 Officers, 1,064 Other Ranks

Results

Canadian railway units constructed, repaired, maintained, operated, and administered all gauges of the entire railway network for the five British Army areas in France and Belgium.

All light railway construction and 60% of the broad gauge was carried out by the CRT.

In 1917-8, 1,404 miles of light gauge and 1,169 miles of broad gauge were laid.

Canadian experiences in railway building through the West easily translated to the devastation of the Western Front. Temporary lines and bridges were a standard way of doing business in the New World, and thus were easily adaptable in any situation in the Old.